O'Connor Brothers, Michael Greenbaum, CBOE Origins & 1977 Teledyne Options

Article, idea or investment stories we think are interesting. Not investment or financial advice.

Recently, I’ve been speaking with some friends who are making investments and trading their personal accounts (“PAs”) more actively. These friends — sophisticated investors — have each, coincidentally, started talking to me about investing in options.

At the same time, I’ve been working through practice questions for the Series 7 exam, which I plan to take soon as part of a longer-term goal to set up an investment fund that could eventually manage outside capital. Options are one of the core topics covered on the exam. Currently, HFW only manages its own money, which in reality is (effectively) my PA.

All of a sudden, I find myself reading about and discussing options almost every day. Although I have a background in investment banking and private credit, I had never really touched or dealt with options directly.

At a high level, like many others, I understood the basic concept:

A put gives you the right to sell a stock at a specific price (the 'strike') — useful if you expect the price to fall, want to hedge a position and / or structure a trade. Various expiration dates are available — daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly and even 2+ years out.

A call gives you the right to buy a stock at a specific strike price — useful if you expect the price to rise, want to hedge a position and / or structure a trade. Again, with multiple expiration dates.

UBS O’Connor

Yesterday, I read a Bloomberg article about UBS exploring a sale of its hedge fund unit, O’Connor to Cantor Fitzgerald. The deal is part of a broader restructuring of UBS’ business — interesting on its own, but what really caught my attention was the name O’Connor 🤔. Why wasn’t it just called “UBS Fund Management” or something similar? In most cases, even household financial names fade away after mergers & acquisitions (think Lehman Brothers or Merrill Lynch).

Why did the O’Connor name last for decades? When you layer on the fact the name actually stems from one of UBS’ predecessor firms, Swiss Banking Corporation (SBC), which acquired O’Connor & Associates in 1992, the name surviving is even more unusual. In 1989, O’Connor was described by the New York Times as “the largest market maker in the financial options exchanges in the United States.”

The name point I’m making may sound trivial to someone outside the financial services industry, but names and their associated prestige matter deeply in finance — especially for recruiting.

I remember when I worked at Lazard in London the newly appointed Chairman at the time wanted to understand more about the firm’s culture. He arranged for a survey to be sent around and replied to (submitted) anonymously that asked about what the firm was doing right, what could improve, what people were proud of, etc. When the Chairman shared the results a several months later, he made it point to mention that what was almost universally agreed upon is high levels of pride in being associated with brand Lazard. If you want to attract talent to put in 80+ hours a week, or endure high stress environments, the name on the door better mean something.

It tells me that finance professionals and UBS saw real and unique long-term value in the O’Connor identity, enough to protect it rather than phase it out. For example, the storied Warburg name, was even phased out just a few years after the merger that formed UBS.

The Secret World of the O’Connors

“O’Connor & Associates was founded in 1977 by mathematician Michael Greenbaum, with funding from brothers Edmund and William O’Connor, according to the book “The Predictors” by Thomas A. Bass, who wrote that the firm “made money hand over fist” and “developed a cult of secrecy.”

- Bloomberg. UBS in Talks to Sell Its Hedge Fund Unit O’Connor to Cantor. By Irene Garcia Perez and Todd Gillespie. May 8, 2025 at 1:12 PM EDT. Updated on May 9, 2025 at 4:02 AM EDT.

After some digging online, the story behind the name O’Connor turned out to be even more interesting than I expected — particularly for its pioneering role in the options markets. The firm played a key role in the creation of the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE), now known as Cboe Global Markets. Today, Cboe remains one of the largest and most influential options exchanges in the world by notional dollar volume, serving as a hub for institutional options trading. (Note: While India’s National Stock Exchange (NSE) now leads globally in terms of contracts traded, Cboe still dominates in terms of the total value of options traded.)

The New York Times published a profile of the standalone firm O’Connor & Associates that ran in September 1982: “The Secret World of the O’Connors.” It’s a fascinating profile of the reclusive O’Connor brothers, sons of a Chicago fireman, and their rise as major market players. Some excerpts read like a movie script.

“The O'Connor brothers - Eddie is 58 and Billy is 52 - are described by acquaintances as quiet men, who shun the social limelight and whose only passions are trading and golf. They made their first fortune trading grain futures, riding the great soybean bull markets of the 1960's and 1970's, when soybeans would zoom from $3.25 a bushel to $12.85 a bushel in less than a year's time. During the five different bull markets of that era, one former soybean trader and trade board official estimated, the O'Connors earned more than $25 million.”

- The New York Times. The Secret World of the O’Connors. By Leslie Wayne. Sept. 12, 1982.

The story about the O’Connor brothers is definitely worth a read, but what really caught my eye was Michael Greenbaum, who also mentioned in the recent Bloomberg article I read. He was reported to be 39 at the time of the 1982 New York Times piece:

“It is under Mr. Greenbaum, who would not return telephone calls, that O'Connor & Associates and O'Connor Securities has flourished. ''If Greenbaum made $10 million last year, it wouldn't surprise me,'' said a former O'Connor associate. ''If he made $50 million, it wouldn't surprise me either.''

Mr. Greenbaum is generally acknowledged as the mastermind of the options activities…”

- The New York Times. The Secret World of the O’Connors. By Leslie Wayne. Sept. 12, 1982.

How could I not look into this further?! But this is where the name and historical intrigue ends — and where the story becomes even more relevant from a learning perspective, using a real-life example from a genuine master of the options market.

Teledyne July, 1977 Trade

As luck would have it, I came across a 2023 article celebrating the 50th anniversary of the founding of the CBOE, which included a direct contribution from Michael Greenbaum, the founder of O’Connor & Associates.

“50 years ago, on April 26th, 1973, the CBOE opened its doors and listed option trading began. For the first time, such things as standardized striking prices and expiration dates were available on an option contract.”

- Option Strategist. Celebrating 50 Years of Listed Option Trading at the CBOE. Presented by McMillan Analysis Corp.

In his article, Greenbaum recounts the firm’s first big win — and it’s a masterclass in how professional traders exploit mispriced risk using options.

The Trade, in His Own Words

“Starting with my operations in 1977 we had a field day with the markets. We were always positive gamma, always! Our first “home run” was only a month after our inception, in TDY (Teledyne). It was a firm run by Henry Singleton, an MIT graduate. It was an early conglomerate and actively traded on the CBOE. The day of the July, 1977 expiration, also happened to be their earnings announcement before the market opening and we knew that it was their practice to announce then. The stock traded on that Thursday at $71/share and the market makers in the TDY crowd were only too happy to sell the July 70`s for a little over $1 since they were reasonably certain that the stock would be pinned, as was the usual case, the following day at $70. They based the option pricing on Black Scholes, for the most part, plus their thinking about the pinning. I was salivating all afternoon on that Thursday knowing, with the earnings coming pre market on Friday, that we could have a nice “jump.” We loaded up on Thursday by buying the July 70's and shorting the stock with positive curve. Luckily for us they announced very bad earnings, and the stock was halted for an hour or so on Friday morning and opened down $10 at 60. O'Connor & Associates had our first really major killing with a “back spread.” We made significant money – and all with almost zero downside risk.”

- The Untold Story of the CBOE's Good Fortune. By Michael Greenbaum. Published in 2023.

Let’s Break This Down…

1. What is "Positive Gamma"?

In options trading:

Gamma measures how much an option’s delta (its sensitivity to stock price) changes when the stock moves.

Positive gamma = your position's delta adjusts in your favor as the underlying stock moves, giving you exposure to large price movements. However, whether this leads to profits depends on timing, volatility, and other factors.

Negative gamma = your position’s delta moves against you as the stock moves, which can lead to losses from large price swings. These positions typically benefit when the stock stays within a narrow range (i.e., “pinned”).

Suppose you buy a call option with a $90 strike while the stock trades at $85. If the stock rises to $89, the option becomes significantly more valuable — even though it’s still out-of-the-money — because its delta increased sharply (i.e., the option is much closer to being in the money at $89 vs. $85). That’s positive gamma in action.

So, what Greenbaum’s saying is his and O’Connor’s trading philosophy was built around owning convexity — always having a position that gains from large movements — “We were always positive gamma, always!”

2. The Setup: A Mispriced Event

The trade took place on the Thursday before Teledyne’s July options expiration — the last trading day before the contracts expired on Friday.

Teledyne’s stock was trading at $71.

Call options with a $70 strike were trading for a ~$1, implying low expected volatility. The market expected the stock to be pinned, or stay around $70.

O’Connor’s Greenbaum knew earnings were coming pre-market on Friday — something the market had mispriced or overlooked. The call option wouldn’t expire until the end of the day.

This created an opportunity: the market was pricing the call as if no earnings volatility would impact the stock before the call expired, even though earnings were confirmed for the next morning.

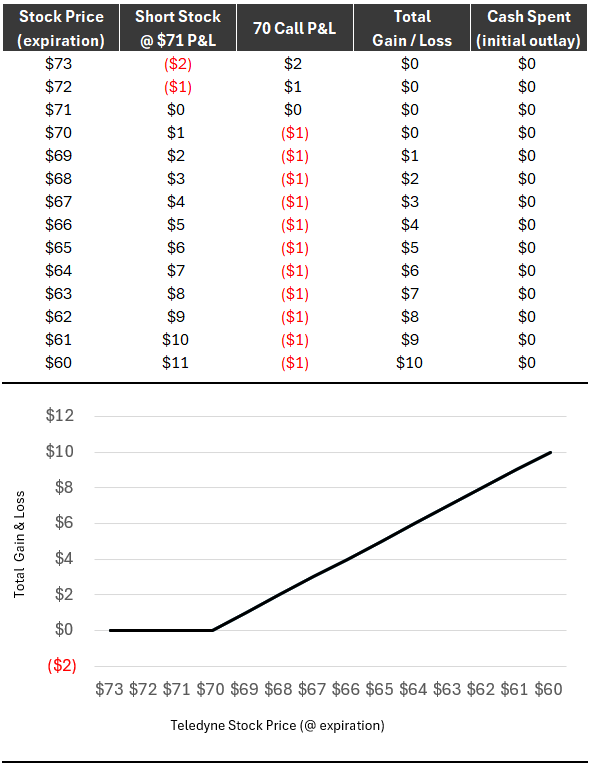

3. Trade Construction

Greenbaum’s team entered into a structured options trade with the following key components:

✅ Long July 70 Calls @ ~$1

Gives the right to buy the stock at $70 before the end of the day Friday.

✅ Short Teledyne Stock @ $71

Collected $71 in cash per share from a short sale. The way you short a stock is you essentially borrow shares and immediately sell them, with the idea of buying it back at a lower price when you need to return shares. Here, Greenbaum borrowed Teledyne shares at $71 and immediately sold them. If the stock dropped, to let’s say $65, him and O’Connor would buy back the shares at $65 and return them, making $6 per share on the trade.

What’s more, is that Greenbaum actually used part of the proceeds from the short sale to fund the ~$1 long calls (above), minimizing upfront capital costs.

💡 This combination creates a “synthetic long put” with low cost and high convexity.

4. Why It Worked

On Friday, Teledyne announced earnings pre-market, and Greenbaum’s expectation of significant share price movement was correct.

The stock opened at $60 — down $11 from the prior close.

Although the calls expired worthless, O’Connor only paid, with proceeds from the short sale (!), ~$1 to hedge the trade in case the stock moved higher on earnings.

The short gained $11 ($71 - $60)

The total gain was $10 multiplied by the position size. Remember, the short sale funded the call premium paid of ~$, which limited the downside of the short position.

Result: A massive profit — with limited downside had they been wrong, given they bought call options.

5. Why the Trade Had “Almost Zero Downside Risk”

Maximum gain = Massive, if the stock dropped sharply on earnings.

Maximum loss = Essentially zero. ~$1 premium paid for the $70 call + stock loss on short trade above $71, which would be offset by the calls being in the money.

Probability-weighted view: Greenbaum might have believed the odds of a significant upside move were low (“pinned”), while the potential for downside movement was underpriced. Buying calls hedged the trade in case the stock rose unexpectedly, and any loss on the short position would be offset by gains from the call option being in the money.

This is the definition of asymmetric payoff and positive convexity — the heart of great options trading. The options were priced under the assumption of low implied volatility, despite a known catalyst — a classic mispricing opportunity.